Introduction

Assessment takes center stage in the teaching-learning continuum, assisting teachers in ascertaining students' understanding of prescribed concepts and providingfeedback on learner progress to parents and stakeholders. Assessment also helps to identify areas for improvement in fostering academic growth and achievement by askingthe why, the what, and the how. The “what” is contained in the assessment method to use, and the “how” is contained in the means of ensuring quality in the process and the use of gathered information (Bill, 2021; Manitoba Education, Citizenship and Youth, 2006). A host of studies reveal that teachers’ assessment practices make the case for stronger bonding between classroom assessment practices and students’ progress (CAST, 2024; McMillan, 2013; Westbroek et al., 2020). Assessment, an empirical tool for proving learning has occurred regardless of students’ abilities, ensures educators think through ways to improve pedagogical qualities to enhance teaching practices. Some studieshave been conducted on differentiating assessments in culturally diverse settingselsewhere (Al-Mahrooqi& Denman, 2018;Arsyad &Suadiyatno, 2024; Marlina et al., 2023). Asidefrom the above considerations, disparities persist in the context of Manitoba, Canada's Indigenous milieu, particularly in the newly introducedland-based education (LBE) in northern schools (Education and Early Childhood Learning, 2025). Mindfulness is required to underpin the significant change (Davis & Dart, 2005) imperative in considering and closing the equity gap for deeper education to occur as pointed out by Appiah-Odame (2024,2025). All theassessment forms provide information, but the assessment for learning (AfL) provides a better understanding of learners' abilities through continuous interaction in effective instruction (prior to) and post-assessments for inclusivity.

Conversely, the traditional assessments, alternative tostandards-based assessments (SBA), are rigid, and place more emphasison a linear/uniform approach to examinations for all students, and poorly address inclusivity in meeting individual needs, interests, and weaknesses of students.According to Quansah, the classroom has become increasingly inclusive in recent times, with students from diverse backgrounds present. This diversity necessitates the use of assessment tools that are tailored to individual needs, rather than a one-size-fits-all approach, which calls for the expansion ofbest practices (Quansah, 2018). Differentiated assessment (DA) (Ali, 2015) is an alternative assessment method that focuses on applying knowledge and skills to real-life situations,taking into accountindividual student capabilities (Appiah-Odame, 2025).The Assessment for Learning (AfL) approach addresses mixed abilities and diverse needs, supports academic flexibility, and enables progressive analysis for excellence with data (Tomlinson, 2015, 2018). It allows students to choose their assessment style and demonstrate broad-basedresolution to student learning (Kajitani et al., 2020). In conducting ongoing formative assessments (FAs) and performing diagnostic analysis on accumulated data, teachers can identify areas of strength and weakness of individual learners and tailor instruction accordingly before reaching a summative assessment.

Some teachersattempt to identify areas of individual special learner needs through differentiated instruction, yetstill get trapped in practicing what alignswiththeone-size-fits-allapproach to assessment. Marlina,Kusumastuti, andEdiyantostated there is a need to move beyond this awkward approach to one thatappeals to differentiated assessment strategies (DAS) (Marlina et al., 2023). The traditional straight assessment system is one of theoutdated practices that places less emphasis on meetingthe diverse needs of all learners. Alternatively, DA is one of the effective assessment strategiesthat teachers use, aside fromteaching to diversity (Katz, 2012), to gather information on students’ progress (Tomlinsonet al., 2015). There must be strategic plansin place to effectively gauge the diverse potential each student brings to theschool.DA promotesdivergence in creative thinking in teaching and learning, providing information regarding students' progress (CAST, 2024; Rajak & Dey, 2025),through strategic planning (Suprayogiet al., 2017; Tomlinson, 2015). However, as mentioned by Katz (2012), teachersplay a crucial role in addressing the diversities among learners, including their characteristics, backgrounds, learning abilities, styles, preferences, needs, adult support, experiences, and interests (Moon et al., 2020; Westbroek et al., 2020). Therefore, differentiated assessment seeks practical approaches in providing flexibility not only to students, but also, to teachers in the levels of knowledge acquisition, skills development, and types of assessments to offer students.

Differentiated assessment strategies (DAS)are a panacea, facilitating teachers to perform critical,effective instructional planning in offering choices to the learners. More recent studies by Appiah-Odame (2025),Anggraeni(2018), and Lawrence et al. (2019) point out the need to infuse technology-based innovation in teaching and learning methods vital to cater todiverse student needs (Marlina et al., 2023;Moon et al., 2020; Westbroek et al., 2020). When a teacher has information abouta student's learning profile, they havethe advantage of becoming aware of the struggles of the learner and employ strategies suitable through effective planning to meet them at the point of their needs through regular reviews.

Literature Review

Differentiation viewpoint is to meet diverse learners’ various academic needs, and it is a decision-makingprocesswithin complex practices in the education settings. This paradox exemplified in schools is essential as teachers face internal constraints in pursuit of heuristics to tacklethe complex workload that includes time tabling, gathering resources, planning for instruction, assessments, evaluations,and reporting (Majuddinet al., 2022; Westbroek et al., 2020). Moon et al. (2020)assert that differentiated assessments offer choices to learners in conducting assessments, aimed at developing abilities to align withthe many unique learning styles. Furthermore, DA enhances flexibility in learningprogress as a new paradigm (Noman & Kaur, 2020) by removingbarriers that allow learners to fall through the cracks, thereby permitting teachers the flexibility to avoidoverburdening students with tentative set assignment submission dates (Moon et al., 2020). When teachers endeavor to remove the hidden barriers, they set the toneby considering individual learning styles in classrooms through accommodations, flexibility, adaptations, and modifications, and by providing adequate support to acceleratelearning for all.

Therefore, differentiated assessment is an effective assessment practicethat allows teachers to accommodate and modify practices, including assessments, to meet the individual needs, abilities, and learning styles ofdiverse classrooms (Nivera, 2017; Quansah, 2018). Instead of employing a one-size-fits-all assessment method, the DA method solicits techniques to better support unique strengths and needs for all learners using tri-facet components: “For,” “As,” and “Of,” learning (Manitoba Education, Citizenship and Youth, 2006). Just as pragmatic in freedom for analyzing test scores isthe requirement for all teachers to relieve stress during evaluations and to encourage students. The DA also extends leverage in equity for all learners by demonstrating learning through multiplelenses. Hence,a differentiated assessment approach enhances student-centered testing, encompassing pre- and post-assessment planning and information gathering in the form of diagnostics and formative assessments, which leads to the summative assessment as the finalpart of the assessment continuum.

Gathering Information

By asking focused questions in class,teacherselicit understanding, which can be conducted through observations and systematic observations of students as they process ideas.Misunderstandings and associated gaps, some of which are linked to mental and physical health issues, are revealed in student knowledge, as noted by Nelson et al. (2020),and there are varied methods for data gathering. Some include homework, learning conversations or interviews, presentations, quizzes, tests, examinations, richassessmenttasks, computer-based assessments, learning logs, as well as projects and investigations. All these methods find their applications grouped into diagnostics,formative, and summative assessments for collating information leading to reporting.

InterpretingInformation

The developmental continua,checklists, rubrics, reflective journals, self-assessments, and peer assessments comprise a comprehensive set of methods for describing and interpretinginformation. The developmental continua profiles, according to Bill (2021), describe student learning to determine the extent of learning, the next steps, and to report progress based on achievement, which isimportant to teachers, students, and families. The use ofchecklists and rubrics for record-keepingserves to describe the criteria necessary for consideration in understanding students’ learning, and with gradations of described and defined performance.

Records Keeping and Communicating

Keeping records comes in many forms, such as anecdotal records, student profiles, video or audio tapes, photographs, andportfolios. The anecdotal notes are focused, descriptive records of observations of student learning over time using running records (Rodgers et al., 2021). Student profilesprovide information about the quality of students’ work as related to curriculum outcomes in conjunction with theindividual learning plan (ILP or IEP). In rethinking assessment (Bill, 2021), students communicate their learning outcomes to teachers through demonstrations, parent-student-teacher conferences (PSTC), records of achievement, report cards, and through learning and assessment newsletters (Rodgers et al., 2021).Teachers who vary the opportunities for students to communicate, not only through paper-and-pencil methods but also through other mediums such as periodic symbolic representations, report cards, and PSTC, where parents can offer ideas and suggestions for planning, creategreat schools.

Research Objectives

The reason for this study is tolay outthe effectiveness of DA protocols in a multi-level learning inclusive classroom through a specific design in terms of:

How to implement and adapt

The benefits of DA to diverse learners and teacher analytic freedom, and

The associated challenges and possible remedies.

Methodology

Research Design

This researchemployed a qualitative document review method, drawing on a larger dissertation, to investigatehow differentiated assessment (DA) strategies serve as viable methods for diverse learners in an inclusive learning environment. The researcher used articles published between 2005 to 2025, searched throughEBSCO, ERIC Database,ProQuest, University College of the North library, Google Scholar, Taylor and Francis, and ResearchGate. The research “wild cards” used to retrieve links used for this purposeinclude“inclusive classroom,” “diverse learners,” “learning profiles,” and “differentiated assessment.” The retrieved articles were skimmed and scanned thoroughly, and only those thatspoke to the topic under construction and fitthe research objectives were selected for detailed reading. The main research questions to delve into DA are:

Research Question 1 (RQ1): What is assessment, and what do you understand by differentiated assessment?

Research Question 2 (RQ2): How do you differentiate assessment?

Teachers are aware of the impact of assessment and its results on student life in boththeshort and long term. Theresearchers' decisionto employ a document review method was driven by the purpose of fostering a sustained interest in lifelong learning. The approach enabled an in-depth discussion of the best practices, drawing on insights from four participants. The four candidates were selected from an earlier pool of eleven volunteers whose datawere originally collected as part of a larger dissertation study, and each of these participants brought over a decade of teaching experience to the analysis, as reflected above in Figure1.

Sample Data Collection

Drawn frominitial dissertation research, the study population consisted ofrural and urban high-need schools. The four teachers whoparticipated in this research, reflected in Table 1, were selected who teach any or combinations of mathematics, science, physics,and biology.

| Participant code | Grade level of teaching | Degree(s) and content area | Number of years in current teaching position | Years of application of effective evaluations (SBG) |

| A-JT (M) | 7 -12Rural | 2 Bachelors, 2 MastersMathematics and Sciences. | 13 | 13 |

| D-BH (M) | 9 – 12Rural | BachelorsMathematics, Chemistry, PhysicsYearbook. | 19 | 19 |

| E-MC (M) | 9 – 12Rural | BachelorsMathematics, Sciences, Physics, Biology. | >10 | >10 |

| C-MA (M) | 9 – 12Rural | BachelorsMathematics and Sciences. | 23 | 22 |

Figure 1. Participant Biography

All four candidates were males and aged from 35 years to 55 years. The researcher interviewed these teachers and collected information, including sample documents pertaining to differentiation assessments. The study identifies commonalities and differences between teacher practices andexplains themin the analysis of the two research questions.

Data AnalysisProcedures

Research Question 1 (RQ1): What is assessment, and what do you understand by differentiated assessment?

Information to the extent to which these teachers applied assessment for learning (AfL) in lessons was collected and analyzed:

Two lesson plans,a copy of the written evaluation, and an Excelspreadsheet of test score data were produced by all four teachers. The information and documents embody howAfLwas documented. The application of heuristics/educatedguesses, as given in Table 1 by the teachers,gave insight into complexities or uncertain situations arising duringdecision-making.

The perceptions of teachers on planning and discharge of lessons were investigated by measuring the perceived impact of their goal system. Through interviews, the perceptions of selected teachers were collated from their comfort places, which included the jurisdiction of where they teach, home,or offices (Ngozwana, 2018;Veledo-de Oliviera et al., 2006). The teachers constructedagoal system by listing points orusinga Venn diagram as a response to the following:

Brainstorm a specific group and a particular lesson you would instruct.

Design a lesson segment that aligns to your specific group. What are your modalities/steps when instructing this lesson, and describe in snapshot of this lesson?

Why did you implement the selected lesson(s) in a specific way and its importance?

Allfour participants with over ten years of teaching experience were interviewed at their convenience from home, in the classroom after school, or in the office, and each session lasted not exceeding 30 minutes, either by Zoom(video) or WhatsApp (video). The purpose was to observe the behavior and mindsets (Dweck & Yeager, 2019) as participants discuss their planning, creating,anddischarge, and how they mark students’ work.They were asked if there was a change in mindset because of taking part in this research and adapting their goal system (GS) by re-writing new ones.

Analysis was aimed at differences between prior- andpost-intuitionregardingGS, considering: (1) assessment for learning (AfL) into lesson segments, and (2)recalibratingthe previous set goals to one of higher order goals (HOGs):

Teachers audit new goals as they emerge, whether a decline or progress was made with the application ofAfLlessons,

Table 1. Framework for Analyzing Lesson Designs

| Item | Design Purpose | Criteria for Design |

| 1 | Diagnostics assessment | First Step - The teacher thinks about the specific group grade level in assessing in small steps conceptually. |

| 2 | Formative assessment | Second Step - In using the *GRASP method, the teacher moves between desks to check every step by each student before giving the pass to continue to the next stage from “given” to “required.” For example, a student should be able to write out the given parameters in a preamble/question, for instance, in a Manitoba curriculum science grade 10 motion.Third Step – The question invites the learner to produce a suitable formula applicable to the question. |

| 3 | Group assessment | In the Fourth and Fifth Steps, the teacher allows students the freedom to form their own groups of 3 or 4 to problem-solve the question. Upon arriving at the answer, they paraphrase. The purpose is to integrate numeracy and literacy into science, embodying the key objectives of the lesson. The interest in the use of the GRASP stepwise method is to ensure a four-tier level, as this avoids or eliminates students scoring zeroes on an assignment. The scores were tabulated in an Excel spreadsheet, coded with colors and others with boxes. |

GRASP –Given,Required,Analysis,Solution,Paraphrase.

For goal achievement, teachers ascertain if therehasbeenanegative or positive impactonthegoal because of implementing the principles ofAfLlesson segments, considering portions of the GRASP in table 1 (appendix A), principles applied in science, mathematics courses,or other academic subjects.

Changesobserved in the lesson segments in individual classroom practices could be linked to changes in goal achievements and observed patterns inthegoal(s) identified. The researcher, through discussions with each participating teacher, performedananalysis as a member check on howthe proceedings transpired in classroom lessons, with the aim of interpreting the findings.

Research Question 2 (RQ2): How do you differentiate assessment?

In the earlier,larger dissertation, the researcher dwelled on authentic evaluation to motivate, and in this exercise, the emphasis is on authenticating differentiated assessment in this article as a means of best practice to mitigate the cost of meetingthe diverse needs of alllearners.AfLhappens throughout the learning process and is used to provide feedback to students, parents,and teachers to allow for adjustments to ongoing instruction and learning activities. Teachers were asked to elaborate their responses to the interview question based on an aspect specific to their choice in their teaching and how they collaborate with learners in performingAfL. Collaboration is based on desirability levels with the probability of determining the expected gains or shortfall made on the set goals system (SGS).

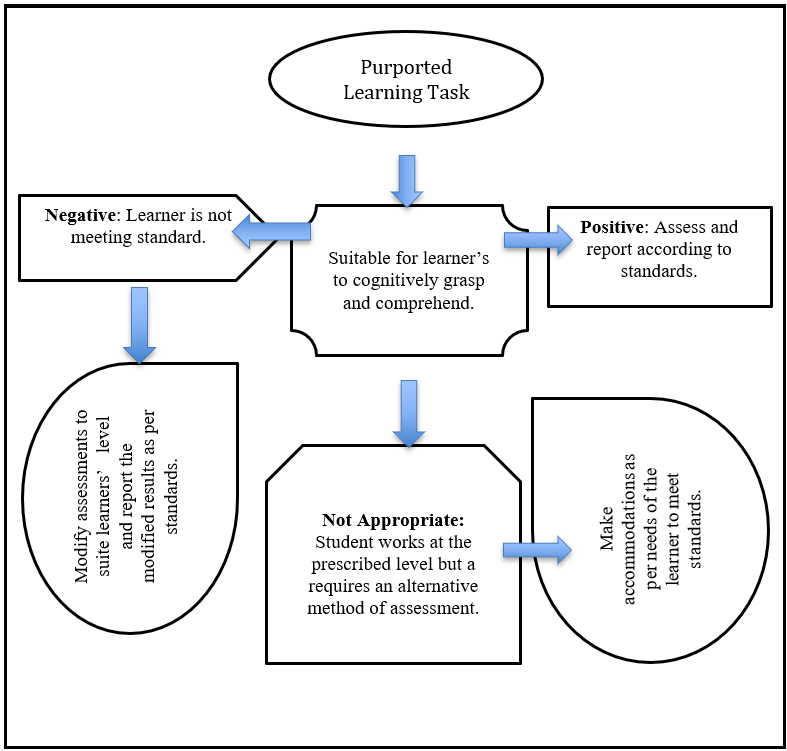

In determining the expected gains, the assumption of teachers relying on standardized systems, and not on meeting set goal systems (SGS) asa shortfall in educating is backward, as it invites the one-size-fits-all practice and does not supplement the standards-basedgrading (Brown, 2022). Differentiation is the right approach to extend support to all diverse learners, and to present the concise assessment task frame of report to inform ongoing learning for both educators and learners (Noman & Kaur, 2020). In a typical assessment task, the four co-researchers allude as diagrammatically depicted in figure 2 above, that in the secondary school grades in science and mathematics curriculum in Manitoba,for instance, some students can fulfill only the cluster zero outcomes while others can perform at higher order thinking levels.

The argument holds thatan easier assessment to motivate the struggling students to do better by performing at the cluster zero level is a surety to justify thatlearning has taken place. The institutional deficiencies identified inunderstaffing and logistics are some stumbling blocksthat lead some teachers to a lackadaisical approach to implementingthese innovativeAfLstrategies in the classroom (Arsyad&Suadiyatno, 2024; Lestari & Yusuf, 2025). The institutional deficiencies do notamountto presenting the weakness in the grades achieved compared to the gains made through performance tasks by such students in demonstrating abilities.

Figure 2. Flow Chart of Assessment Task

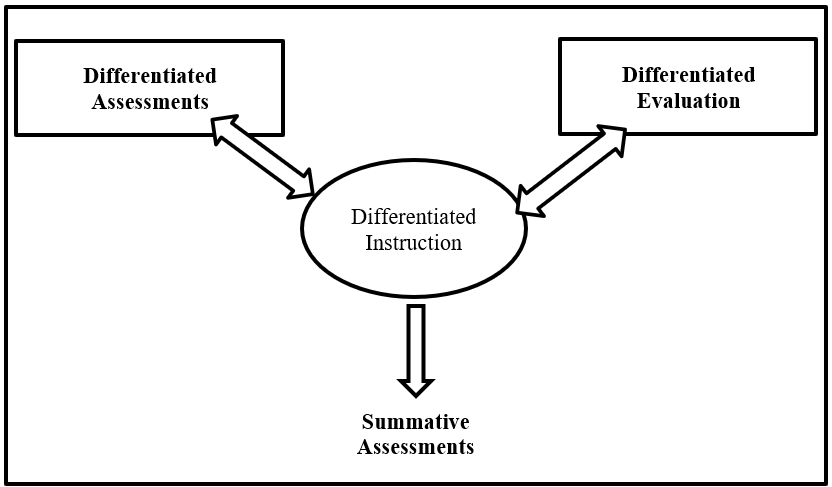

With reference to the above figure, which differentiates assessment and results, if the tangent does not fit (a shift to the left), the teacher revisits the material to make modifications, adjustments, and re-administers itto learners. Repeat the cycles asdepicted in the flow chart in Figure 2 above until the student demonstrates understanding, as shown in Figure3.

Figure 3. The Tri-directional Concept Map to Effective Teaching-Learning

Findings/Results

Academic Adaptability of Differentiated Assessment

In a multi-level learner’s classroom, diversity among the learners' needs persists in varying learning styles, and all teachers who engage learners prepare them to become critical thinkers able to express themselves in ways thatsuitlearning styles. Findings from CAST (2024), which align with the tenets of this research discourse, point out that when learning goalsystems (SGS) are clear, assessments confirm learners’ achievements in prescribed goals. The ideals of the Universal Design Learning (UDL) principlesdepend on teachers and schools applying flexibility in assessment practice, spanning across curricula(Katz, 2012). Building on the importance of flexibilitythat UDL brings, in terms of what, how, and why, it has become necessary to considerhow assessment practices reflect and support adaptability, ensuring that all learners demonstrate learningwith reduced inherent distractions.

Providing learners with meaningful and authentic assessment options, they are better positioned to engage deeply with the content,and such opportunities are not only to accommodate diverse learning preferences. Such deeper engagements also empower students to demonstrate their understanding in ways that align withtheir preferences, understanding of individual strengths,and contexts. Teachers effectively differentiated based on students' readiness, interest, and learning profile, with all four teachers making adaptations for all to demonstrate understanding in ongoing assessments (Kaur et al., 2018). Nevertheless, DAsare valuable applications in various subjects, particularly as formative assignments (FA), and they requirecritical reflection, planning, and dedication from teachers and all stakeholders.

Benefits of Differentiated Assessment in Multi-Level Classroom

Based on the targeted learning goals, teachers, students, parents,and stakeholders’ benefits. Teachers share the criteria “how they assess in different contexts of learning,” and as feedback, and learners get evidence about their learning status to decide where they are and what they need to do or improve further. During the assessment, teachers keep in mind the strategies for sharing the intended learning goal of the lesson before, during, and after the teaching-learning process (Brookhart & Lazarus,2017; Rajak & Dey,2025). Whereas targeted support through scaffolding and stepwise adaptations is crucial for learners with disabilities, ensuring equitable learning outcomes also requires alignment between instructional strategies and assessment practices.

Despite efforts to differentiate instruction, many teachers lack sufficient knowledge asidefromresources for the effective implementation of DA, and this gap highlights the need for further exploration into how assessment can be tailored to meet diverse learner needs. Further observations on effectiveimplementation techniques made by Appiah-Odame (2024,2025) indicated thatsome teachers are well content with differentiated instruction practices.However, the majority of teachers still lack the temerity to dig deeper into differentiated assessments to impact authentic evaluations. This research study, which led to Appiah-Odame's (2024) research, was drawn from a larger dissertation in 2023, bearing relevance tothis study. This researcher highlighted in the study that the educational departments in Manitoba and other provinces of Canada predominantlyfollowthe standardized test as the assessment practice criticized by Appiah-Odame (2024) and Wilson andNarasuman(2020). However, other studieshavenoted that offering choices (Escolano&San Jose, 2025) to learners for preparing whiteboard or video presentations, oral presentations, project-based assessments, portfolios, and problem-based assessments as facets of performance tasks encourages diverse learners to self-actualize for progress. One such monitoring strategy was the use of the “wall décor” where students can track submitted or unsubmitted work and how to consult with a teacher to complete projects (DeGree, 2025;Manitoba Education, Citizenship and Youth, 2006).

Discussion

Figure 1 provides the information on all four co-researchers and the findings from their data. In the following paragraphs the research discusses in detail the noted patterns emerging from contrasting views.

RQ1: What is assessment, and what do you understand by differentiated assessments?

Findings showed that all four respondents designed, instructed, andsupervised many forms ofAfLafter several years in honingskills onflexibility, adaptations, modification, and support for accelerating learning. Asan anecdote to RQ#1, all the respondents understood assessments and how to differentiate, but they gained more open-mindedness in the application to critically consider what benefits each learner'sacademic disposition.Despite these provisions, there are still pressing challenges in schools regarding teachers’ best practices, particularlyin differentiating assessments. Some ofthe pressing challenges in individual avocations include inadequate resources, personnel, and infrastructure, which aremajor issues impeding the implementation of differentiated assessment strategies in the classroom. The teachers indicatedthat they became aware of how to align best practices with learning objectives (GSs) as positedby Lestariand Yusuf(2025),andArsyadandSuadiyatno(2024) through concerted efforts without giving up. Institutional understaffing and deficiencies in logistics hindered the implementation of innovative AFL policies in classrooms,asArsyadandSuadiyatnonoted. Theprovision of adequate classroom staff support by school districts/boards would help teachers align the best authentic, differentiated education as a measure to curtail student failures, as shown in teachers’grade books.

Research Question 2 (RQ2): How do you differentiate assessment?

About how to differentiate in assessment (RQ#2), the effective implementation of innovative strategies calls for adequate teacher training. There are still challenges withimplementing effective protocols for practicing differentiated assessments and identifying existing gaps to provide adequate feedback to students, enablingthem to relearn as critical thinkers. The lack of opportunities for professional development or overwhelming workshops fits the description shared by Lestariand Yusuf(2025). The descriptor points out that, aside from the school-work overload, which includes the reluctance of teachers to effectively spend extracurricular hours aligning new developments with time-consuming but eventful practices geared towardlearning objectives. Implementing differentiated assessment strategies in the classroom may be time-consuming for most educators,including teaching administrators. The general tendency of valued changeproposals is to attribute the change to a deficiency in teacher knowledge, aspirations,and skills dispositions.

In large classroomswith multi-level learners, diversity is a crucial concept that teachers must address, as they need to prepare multiple versions of assessments, provide targeted feedback, and monitor learners’progress. In present-day classrooms, teachersoften multitask and become overburdened and overwhelmed with numerous activities and multiple duties andresponsibilities (Mapepa& Magano, 2018). A means to ensure all students’ success predicates according to respondents’ views, on how teachers are abreast with the tr-directional model in figure 3, to be able to swing between differentiatedinstruction, assessment, and evaluation,before justifying learning is completed by performing a summative assessment. Participants stated that implementing DA strategies in the classroom is complex in scope in terms of planning and execution. Lestariand Yusuf(2025)found that demand from teachers who prepare and adapt aspects of the prescribed curriculum makes sense in the bid to meet the multi-level needs of learners in the domains of testing, where teachers align these elements with students’ needs, interests,and characteristics (Gaitas &Alves, 2017). Resistance to adopting a new approach is one of the constraints to effectively implementing DA strategies. Some studieshave revealed that educators are deeply rooted in traditional evaluation methods instead of standards-based approaches, which validates the “one-size-fits-all” mindset andthe accompanying struggles of accepting most significant change (Davis & Dart, 2005) in adopting new dimensions to assessments (Westbroek et al., 2020). Teachers’ self-efficacy and constructivist beliefs are necessary for effectively implementing DA strategies through assessment for learning (AfL) into lesson segments, andrecalibratinggoals to higher order goals (HOGs) by teachers.

Teachers with low self-efficacy are not likely to implement these innovative assessment strategies in the classroom. Inference fromSuprayogiet al. (2017)revealed that all the above encounters can be mitigated and require a multifaceted approach. One of the requirements is that teachers are retrained to enhanceneeded skills and knowledge through professional development (PD). The ongoing PDs help in building and sustaining teacher confidence to implement DA strategies effectively (Gaitas &Alves, 2017). Therefore, with all these strategies, schools and teachers cansuccessfully implement differentiated assessment strategies in classrooms to promotelearner progress.

Conclusion

The relevance of this research finding echoes that assessment should not be viewed asastand-alone from instruction as well as evaluation, but rather, as an integral embodiment of the teaching-learning-assessment continuum in line with findings from Nomanand Kaur(2020) tied to respondents’ perspectives. The tri-directionalteaching model (Figure 3) involves learning and testing, which includes differentiated assessment (DA), a tool used to determine reframed differentiated evaluation (DE) and instruction (DI), and vice versa, forany of the three. Differentiated evaluation is a dismissible norm of practice to many teachers,but has become admissible as a determinant tool for justifying students’ mastery of concepts enshrined in a department of education curriculum. When DA and DEoccur early during the formative stages of learning, they become essential tools for adjusting the learning continuum for students in transitionyears. By differentiatingassessment strategies, passive learners are empowered, and instructors develop strong bonds,free from fear ofexpressing their opinions, whether in words or writing.

The success of students relies on prompt feedback from teachers to enable them to reach intended goals, and the successful implementation of DI and DA,as the learning objectives do not change in scope for all the assessments, whichare part of the motivation,as purported by Kaur et al. (2018) and Nomanand Kaur(2020). Teachers rely on differentiated assessments to determine the meeting point of a learner’s styles, needs, and perceptions to become active in the learning process in a multi-level learning classroom. Such ways of knowingemerge through critical reflections, resource allocation, planning, and instructional feedback to students, parents,and school divisions/boards. The expressed strategy of DA ensures equity, enabling all learners to become effective in theirlearning, and its execution enables teachers to align withinclusivity and equal access in a multi-level classroom.

The researchinvestigated teachers' beliefs about implementingdifferentiated assessments in a multi-level learning classroom, as well as alternatives to traditional examination methods. Such heuristics offered teachers the impetus to seek ongoing professionaldevelopmenton how to perform critical assessments. The insightprovides new perspectives on offering students feedback, delivering it in flexibletimes, grouping tasks, avoiding standardized (centralized) examinations, avoiding zeroes, and resourcing students to facilitate taskcompletion (Ali, 2015; Appiah-Odame, 2025).The research revealedseveral challenges, including teacher preparedness, pedagogical practices, instructional styles, and institutional adaptation, particularly in how teachers use and value heuristics/alternatives when implementingdifferentiated assessments. The challenge of institutional timemandates a framework within which teachers must initiate and complete certain assessment tasks, asenshrined in the semester system for educating by school districts/divisions/boards,should be fluid. Teachers should offer extra timeto make accommodationsfor diverse learners to accomplish their tasks to ensure equity and fairness to succeed.

The purported DA learning task model is suitable forlearners’ cognitive development for grasping and comprehending, and hence, a teacher, through observation of the positives in learners’ growth, performs summative assessment(s) and reportsprogress. When a learner is not meeting standards, it behooves the teacher to modify assessments to suit the learner’s needs and level of assimilation and then report the modified results accordingly. There are situations where learning tasks are not appropriate. Students work at prescribed levels, whichcan be below or above, but require alternative means of assessment, including analyzing, observing, questioning, peer assessments, and self-assessments. Othercompendia of venues for best practices consider conversations, performance tasks, projects, unit tests, and hands-on laboratory practicesas science teachable and land-based learning (LBE). The onusrestswith a teacher to make such accommodations to meet learners’ needs.

In conclusion, this research is asmall-scale and interpretive study, and generalizing the findings will be speculative, considering the teacher's acceptance of the use of strategies, implementation, beliefs, attitudes,and behaviors. Whileutilizing DA ideals, it is also necessary for teachers to struggle with effective time management for handling multi-level learners. However, allowing for multi-day tasks with guidance offersstudents the support needed to complete tasks.

Recommendations

Data from four teacherswere collected from experienced teachers in middle and high school mathematics, sciences, and other related courses, which created a gap in authenticating the study findings and weakened the credibility of the revelations aboutbest assessment strategies that can be applied elsewhere. The research, which takes views and perspectives from only four teachers and generalizes the results, has a bias in proving the objectivity ofstudent success and teacher efficacy. The research proposes that future examinations on this topic could expand the sample size to offer deep insight as to how teacher perceptionsofdifferentiated assessment evolved over time in connection with progress in student learning. Other investigations can be performed witha learning interest for a particular northern Indigenous community in Manitoba, Canada,or elsewhere.

Limitations

The findings from the focus group study,based on extensive research conducted earlier, indicated that traditional teachers are overly reliant ontraditional ways of performing assessments.Traditional assessment practices provide numerical grades that raise suspicion due to the tendency for teachers to overlook the diverseabilities of students. Participants may not have takenakeen interest in reporting all the details of what really pertainedregardingstudents’ progress witnessed through continuous observations in their classrooms

Ethics Statements

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Aspen University in Denver,Colorado, in the United States of America. As per the institution’s standards, participants’ written consent has been collected and preserved by the author. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study by the researcher, and a copy of the Review Ethics Board of Aspen University is attached to the appendix (B).

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that no competinginterests exist.

Generative AI Statement

The author has not used generative AI or AI-supported technologies.