Introduction

Improving classroom assessment has emerged as a global priority for enhancing student learning, particularly in mathematics education, where misconceptions often persist undetected without timely feedback. Over the past two decades, a growing body of research hasdemonstrated that assessment practices embedded within instruction, often referred to as formative assessment or assessment for learning, can significantly enhancelearning outcomes across subjects and age groups (Black & Wiliam, 1998;Suurtammet al., 2016). This shift has led to renewed attention on the role of teachers in designing, interpreting, and using assessment information to guide instruction. Effective assessment is no longer viewed solely as a mechanism for grading but as an instructional tool that supports student engagement, differentiation, and deeper conceptual understanding (Nasir et al., 2024; Ngunjiri, 2022; Popham, 2011).

However,realisingthis vision of assessment as a driver of learning remains a major challenge. Despite global policy momentum, studies across diverse systems have found that teachers are not adequately prepared to implement formative assessment principles in their classrooms. High-stakes accountability environments have often led to increased test preparation and surface-level assessment practices rather than meaningful use of evidence to inform teaching (DeLuca & Braund, 2019;Rubeba& Kitula, 2024). Stiggins (1999, 2002) warned that low assessment literacy among teachers – defined as the capacity to design, administer, interpret, and act on assessment information – can lead to inaccurate judgments and reduced learning opportunities. This concern is widely echoed in research, which showsthat pre-service teacher education frequently underemphasizes assessment, while many in-service teachers report feeling underprepared to use assessment data beyond assigning grades (DeLuca & Klinger, 2010; Luitel, 2021; Pastore, 2023). As Leightonet al.(2010) and Hull and Vígh (2024) argue, without a solid foundation in assessment literacy, mathematics instruction risks remaining evaluative rather than instructional in purpose.

These challenges are particularly acute in examination-oriented systems where national testing regimes exert strong pressure on instructional choices. In such contexts, the phenomenon of washback – whereby high-stakes assessments can undermine classroom practices – has been found to hinder the implementation of formative assessment even when policy frameworks support it (Cheng, 2005; Yan & Brown, 2021). International reform efforts increasinglyrecognisethe need for alignment across curriculum, assessment structures, and teacher preparation to enable real change in classroom practice (Brookhart, 2011;Oguledo, 2021). However, successful implementation also depends on how teachers interpret reforms in context and how factors such as training, experience, and professional roles shape their assessmentbehaviours.

In Ghana, School-Based Assessment was introduced to embed continuous, classroom-level assessment into everyday teaching. Although national policy supports formative approaches,anocdotalevidence and policy reviews suggest that teachers continue to rely heavily on traditional paper-and-pencil tests (Kudjordji& Narh-Kert, 2024;Ministry of Education, 2012; World Bank, 2013;). Yet there is limited empirical research examining how mathematics teachers interpret and enact assessment reforms or how individual characteristics such as years of teaching experience, training in assessment, or external examiner roles relate to their classroom practices. Previous studies in Ghana have focused on broader curriculumor assessment implementation (Anamuah-Mensah et al., 2008; Armah, 2015; Iddrisuet al., 2025), early grade assessment (Rose et al., 2019), or general awareness of SBA (Akugri, 2023;Etsey& Abu, 2013)but have not systematically investigated the intersection of practice, perceived skill, and contextual factors in secondary mathematics classrooms.

This study contributes distinctively by providing a national-level analysis of senior high school mathematics teachers’ assessment practices through the dual lens of practice and self-rated skill, and by explicitly linking these to predictors such as professional training, years of teaching experience, WAEC examiner roles, gender, and qualifications. In doing so, it addresses two critical gaps: (1) the lack of empirical evidence from West Africa on how teacher background factors predict both practice and competence in mathematics assessment, and (2) the need to operationalize teacher assessment literacy using measurable domains of practice and skill. This explicit linkage allows for testing expectations that professional development is positively associated with both broader assessment use and higher self-rated skill, while years of experience and examiner roles show weaker or inconsistent associations.

Research Questions

The study is guided by threeoperationalisedresearch questions that ensure one-to-one traceability with the variablesanalysed:

Assessment Practices:What are the mean scores of Ghanaian SHS mathematics teachers on the assessment practice domains (PPT, STDU, CARE, UPA, and TVR), and how do these vary across teachers?

Assessment Skills:What are the mean scores of teachers’ self-rated assessment skills in the same domains (PPT, STDU, CARE, UPA, and TVR), and what patterns emerge?

Predictors of Practice and Skills:How do background variables (assessment training, years of teaching experience, WAEC examiner role, gender, and qualifications) associated with differences in teachers’ assessment practice and assessment skill scores?

Note.PPT = Paper–Pencil Tests; STDU =StandardisedTesting and Data Use; CARE = Communicating Assessment Results, and Ethics; UPA = Using Performance Assessment; and TVR = Ensuring Test Validity and Reliability

Literature Review

Assessment Literacy and Reform Context

Assessment literacy refers to teachers’ knowledge, skills, and dispositions for designing, interpreting, and using assessment to support student learning (Popham, 2011; Tan et al., 2017). Globally, education reforms emphasize assessment as a lever for improving teaching and learning (Pastore, 2023). However, this systematic review of recent research finds that teachers often struggle to implement new assessment approaches in practice. In many countries, including the U.S. and Europe, teacher preparation historically under-emphasized assessment methods (DeLuca et al., 2016; Tan et al., 2017). As a result, even well-intentioned policies (e.g., “Assessment Reform” initiatives) face resistance; teachers report lacking confidence or training in using assessment data diagnostically (Mertler, 2004; Pastore, 2023). For example, surveys in Africa and Asia report low assessment literacy among mathematics teachers despite training (Ahmadi et al., 2022;Akayuure, 2021). These findings mirror those from North America and Europe, where weak or inconsistent teacher assessment skills are widely documented (DeLuca & Braund, 2019; Pastore, 2023). The literature, therefore, highlights a persistent global gap: though assessment for learning is valued in theory, many teachers lack the grounded understanding to enact it.

Assessment Practices in Mathematics Classrooms

In mathematics education, literature emphasizes the dual roles of formative and summative assessment. Drawing on Black and Wiliam’s (1998) formative assessment framework, scholars distinguish between assessment forlearning (ongoing, diagnostic practices) and assessmentoflearning (high-stakes testing). Formative practices may include rich feedback, diagnostic questions, and tasks that inform instruction (Tan et al., 2017). Researchers note that effective teaching typically balances these modes, where teachers use formal tests for accountability but also embed formative checks to guide students (Wiliam, 2011). However, evidence across contexts shows formative approaches are often neglected infavourof summative tests. Studies in high-stakes systems (e.g., curricula with exit exams) report that teachers tend to “revert” to exam-oriented teaching (devaluing formative tasks) when under pressure (Asare & Afriyie, 2023; Yan & Brown, 2021). For instance, a systematic review found that even when national policies endorse regular classroom assessment, actual practice remains dominated by end-of-course exams and homework tests (Pastore, 2023;Rahim et al., 2009). In mathematics, specifically, a range of research studies indicatesthat teacher practice lags behind theory. Adesanya and Graham (2023) in South Africa and Enu (2021) in Ghana observe that many math teachers focus on conventional quizzes and past paper drills rather than using assessment to support learning. These patterns echo broader findings across diverse systems, heavy syllabi, exam accountability, and limited resources often impede formative strategies (Asare & Afriyie, 2023; Yan & Brown, 2021). In short, while the benefits of formative assessment are well documented (Black & Wiliam, 1998; Tan et al., 2017), classroom realities tend to bias teachers toward summative tasks.

Teacher Background and Systemic Factors

Recent work increasingly views assessment practice as shaped by teachers’ professional identities and local cultures. The concept of assessment culture captures how school and system norms (e.g., exam-centric accountability) create expectations that shape classroom practice (Yan & Brown, 2021). In systems where student grades determine progression, teachers may feel compelled to “teach to the test,” reinforcing traditional assessments (Asare & Afriyie, 2023). Beyond culture, teacher assessment identity – how educators see themselves in roles such as examiners, mentors, or diagnosticians – also shapes practice (Looney et al., 2017). Although this study does not directly measure identity, it examines related elements, including how participation in national examiner trainings and professional development workshops may shape teachers’ assessment orientations and classroom practices. Wang(2023) and Yu and Luo (2025) suggest this identity is built through experience and institutional roles and can be relatively stable in exam-driven contexts. Other teacher attributes likewise matter. Empirical research in Africa and elsewhere points to factors like formal training, years of experience, and specific roles (e.g., curriculum developer or examiner) as influencing classroom assessment (DeLuca & Klinger, 2010; Mwembe & Moyo, 2024; Xu & Brown, 2016).

Gaps in Research and African Perspectives

Reviews note that African scholarship often emphasizes broad curriculum reform or primary education, with less attention to secondary math teaching (Comba et al., 2018; Rose et al., 2019). When Africa-focused studies do exist, they frequently describe general shortcomings (e.g., teachers’ limited measurement training) rather thananalysingsubject-specific classroom dynamics. For instance, multiple reports indicate that West African teacher education gives minimal emphasis to modern assessment methods (Bold et al., 2017;Etsey& Abu, 2013). These gaps are notable because international evidence shows the complexities of assessment are often subject-specific. Moreover, existing African studies seldom explore how teacher background (such as professional development or exam-related duties) or identityshapes actual assessmentbehaviours. Existing research rarely interrogates how teacher attributes shape assessment practices, even though such factors are known to be pivotal (DeLuca & Klinger, 2010; Xu & Brown, 2016). The present study addresses these lacunae by focusing on senior high school mathematics teachers in Ghana as a case. While Ghana’s context provides illustrative detail (e.g., theSchool-Based Assessment policy), the phenomena under study–teachers’ assessment literacy, choices between formative and summative practice, and professional factors– are framed within the broader, global discourse on teaching quality and assessment reform efforts.

Conceptual Framework

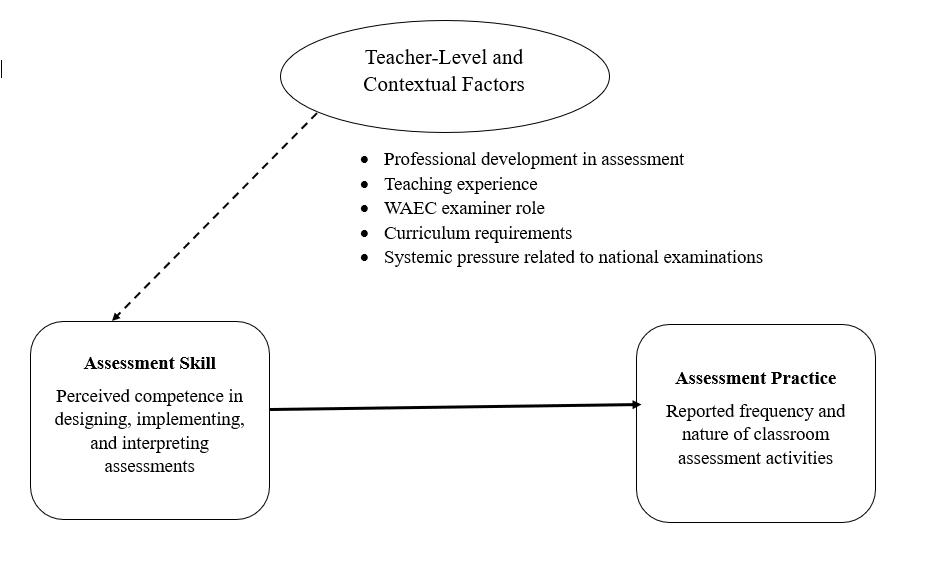

This study is guided by a conceptual framework that positions teachers’ assessment practices as shaped by their level of assessment skill. Two domains are central: assessment practice,which refers to the reported frequency and nature of classroom activities such as administering tests, giving feedback,analysingstudent work, and using assessment data; and assessment skill, which reflects teachers’ perceived competence in carrying out these practices. Skill encompasses the knowledge, technical ability, and professional judgement needed to implement and interpret assessment outcomes in ways that support learning (Abell & Siegel, 2011; Popham, 2011; Xu & Brown, 2016).

While assessmentskills are considered essential for effective practice, theiruse is shaped by contextual and institutional factors, including curriculum demands, school culture, and examination-related pressures. Teacher-specific factors, such as participation in professional development and involvement in national examination roles with the West African Examinations Council (WAEC),are also expected to influence how consistently and confidently teachers assess.

The framework views assessment skill as foundational to practice, while acknowledging the moderating role of systemic and professional influences. These constructs are measured using validated subscales from the Teacher Assessment Practices Survey (TAPS)as detailed in the methodology. Although not empirically tested, the framework offers an interpretive structure for understanding patterns in teachers’ reportedbehavioursand perceptions. These relationships are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Conceptual Framework: Assessment Practices and Skills of SHS Mathematics Teachers in Ghana

Note.The framework presents assessment skills as the key driver of assessment practice, shaped by teacher-specific and systemic factors, including training, experience, WAEC examining roles, curriculum requirements, and exam pressures. It guided data interpretation but was not empirically tested.

Methodology

Research Design

This study employed a quantitative cross-sectional survey design to address the research questions. The survey method was selected to collect self-reported data on teachers’ assessment practices and skills from a large, diverse sample, offering a comprehensive snapshot of the prevailing assessment landscape. This approach facilitated the integration ofmultiple study components, including practices, skills, and teacher background factors,within a single instrument, enabling broad insights into mathematics teachers’ assessment preparedness.

Participants

Data were drawn from a nationwide survey of Senior High School mathematics teachers in Ghana. A stratified three-stage cluster sampling procedure ensured representation across regions and school types. In the first stage, 21 districts (municipal or metropolitan) were randomly selected across the three Ghana Education Service (GES) zones (Northern, Middle Belt, Southern), prioritising those with at least one government-identified low-performing school. In the second stage, a random sample of schools within each district was selected using a lottery method. Schools were assigned numbers based on the GES sampling frame and drawn without replacement, with two alternates per school also identified in advance. In total, 70 Senior High Schools were selected, comprising 30 government-identified low-performing schools, 20 other public schools, and 20 private schools. In the final stage, all mathematics teachers in the selected schools were invited to participate, yielding a final sample of 516 teachers.

To support external validity, the achieved sample was compared with national GES statistics by region and school type. The final sample covered all 16 administrative regions, with proportional representation of urban and rural schools, as well as public and private institutions. Participation rates averaged 92% across sampled schools, with fewer than 5% requiring substitution from alternates.The teacher demographic characteristics in the sample (including gender distribution, professional qualifications, and years of experience) closely reflected the national GES teacher workforce profile, supporting the representativeness and generalizabilityof the findings.

Research Instruments

Data were collected using the Teacher Assessment Practices Survey (TAPS), a structured questionnaire developed by the study to align with Ghana’s School-Based Assessment (SBA) framework and internationallyrecognisedassessment competency standards. The instrumentconsisted of 52 Likert-scale items that measuredboth the frequency and perceived skill level associated with classroom assessment activities. Teachers indicated how often they performed each task (1 = “Never” to 5 = “Always”) and rated their skill or confidence in carrying out the same tasks (1 = “Not skilled” to 5 = “Highly skilled”).

Items were grouped into five conceptual domains based on a review of relevant literature, curriculum policy, and established frameworks of teacher assessment literacy:

Using Paper-Pencil Tests (PPT): quizzes, term exams, item types, and grading.Example item: “I can set essay questions that reflect lesson objectives.”(14 items)

StandardisedTesting and Data Use (STDU): interpretingstandardisedresults, conducting item analysis, and instructional planning.Example item: “I can interpret a percentile rank from a national test report.”(11 items)

Communicating Assessment Results and Ethics (CARE): reporting scores, parental engagement, and ethical standards.Example item: “I clearly communicate grading criteria to students before tests.”(12 items)

Using Performance Assessments (UPA): tasks involving projects, portfolios, and presentations.Example item: “I use student portfolios to evaluate progress.”(10 items)

Ensuring Test Validity and Reliability (TVR): alignment with learning objectives, test content sampling, and item review.Example item: “I check that my test items cover the full scope of a topic.”(5 items)

(The STDU dimension was initially labelledStandardisedTesting, Test Revision, and Instructional Improvement (STTI) but was renamed toemphasisethe role of assessment data in informing instruction.)

Psychometric Properties

The TAPS underwent a multi-phase development process. Content validity was established through expert review by assessment specialists, who provided feedback on item clarity and alignment with policy. Further refinements were made after pilot testing with mathematics teachers in three senior high schools in Accra. The final instrument was context-appropriate and clearly understood by participants.

Construct validity was examined using factor analysis. Principal axis factoring with varimax rotation was applied. Items with factor loadings ≥ .40 and minimal cross-loadings (< .30 on secondary factors) were retained. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure exceeded 0.80, and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was significant (p < .001), supporting factorability. Internal consistency was strong across all subscales, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from .78 to .91, surpassing the 0.70 threshold for reliability.

Classroom Artefacts for Validation

To mitigate the limitations of self-report data, a subset of 35 teachers (randomly selected across regions and school types, representing about 7 percent of the total sample) submitted recent classroom assessment artefacts, including test papers and assignments. These artefacts were coded using a structured rubric that captured assessment type, alignment with curriculum objectives, and cognitive demand. Two independent raters analysed each artefact, and inter-rater reliability was high (Cohen’s κ = .84). Convergence with survey data was examined by comparing artefact classifications with teachers’ self-reported use of corresponding assessment practices.

Data Collection and Procedure

The survey was administered in person in May 2024 by trained research assistants who visited each selected school to distribute and collect questionnaires. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and anonymity was assured by omitting names and school identifiers. Respondents were asked to reflect on their assessment practices over the previous academic year to generate realistic frequency estimates andminimiseshort-term fluctuations. Alongside the Likert-scale items, the questionnaire captured background data, including gender, highest qualification, years of teaching experience, attendance at assessment-related workshops, and whether the teacher had served as an examiner for WAEC. All responses were coded andanalysedusing IBM SPSS software.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, and frequency distributions) were computed for all items and aggregated scales to identify overall trends in teachers’ reported practices and skills(Pallant, 2020).To examine associations between teacher characteristics and assessment profiles, inferential statistics were applied. Pearson’s correlation was used to test associations between years of teaching experience and aggregate scores on assessment practices and skills. Independent-samples t-tests compared scores across subgroups: (a) teachers who had attended at least one assessment-related training versus those who had not, (b) those with versus without West African Examination Council (WAEC) examiner experience, and (c) male versus female teachers. Cohen’s d effect sizes with 95% confidence intervals were reported for all comparisons(Pallant, 2020).

To account for multiple testing, Bonferroni corrections were applied with familywise adjusted alpha levels (e.g., α = .05/3 = .017 for the three subgroup comparisons). Shapiro–Wilk and Levene’s tests indicated no violations of normality or homogeneity of variance, confirming the appropriateness of parametric analyses. For greater analytic precision, multiple regression models were estimated with predictors (training, experience, WAEC role, gender, qualification) entered simultaneously to examine unique contributions to assessment practice and skill outcomes. Results of these models are reported alongside bivariate tests to strengthen inference.

The study relied primarily on self-report data, which reflect teachers’ perceived practices and self-assessed competence. While such data are vulnerable to social desirability oridealisedresponses, measures were taken to mitigate bias, includingemphasisinganonymity and the non-evaluative purpose of the research. Artefact validation corroborated the survey data: nearly all submitted artefacts were test-based assessments, consistent with self-reported practices and supporting the credibility of the reported trends.

Results/Findings

Dominant Assessment Practices in Mathematics Classrooms

The survey results indicate that traditional paper-and-pencil tests are the most dominant form of assessment used by Ghanaian SHS mathematics teachers. Nearly all teachers (n = 515 out of 516) reported giving frequent written tests and quizzes. Activities such as end-of-term examinations, assigning numerical grades, and using standard question formats (multiple choice, short answer, and essay questions) were reported as being done “often” or “always” by the vast majority of teachers. The mean frequency ratings for these activities ranged between 4.1 and 4.3 on the 5-point scale.

A summary of the mean frequency and perceived skill ratings for all domains is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Mean Score (with 95% CIs) for Assessment Practices and Skills by Domain (N=516)

| Domain | Practice Mean (CI) | Skill Mean (CI) | Practice-Skill Gap |

| PPT (Paper–Pencil Tests) | 4.31 [4.25, 4.37] | 4.24 [4.18, 4.30] | +0.07 |

| STDU (Standardised Testing & Data Use) | 2.41 [2.33, 2.49] | 2.62 [2.54, 2.70] | –0.21 |

| CARE (Communicating Results & Ethics) | 3.75 [3.67, 3.83] | 3.82 [3.74, 3.90] | –0.07 |

| UPA (Use of Performance Assessment) | 2.68 [2.60, 2.76] | 2.91 [2.83, 2.99] | –0.23 |

| TVR (Test Validity & Reliability) | 3.10 [3.02, 3.18] | 3.36 [3.28, 3.44] | –0.26 |

Note: Detailed results are in the appendix (Table A1 and A2)

As shown in Table 1, teachers reported high reliance on traditional paper-and-pencil tests, reflected in both practice and skill ratings. By contrast, the lowest domain means were observed forStandardisedTesting/Data Use and PerformanceAssessment, with self-rated skills slightly higher than reported practices, suggesting awareness but limited enactment. The largest gaps between practice and skill means were observed for Test Validity & Reliability (–0.26) and Performance Assessment (–0.23). Across all items, the overall mean score was 3.21 (SD = 0.48), indicating a moderate level of self-reported competence.

Teachers also reported frequent use of quizzes or short tests during the term, with average frequency ratings around 4.2 (SD ≈ 0.8), which corresponds to between “often” and “always.” These results confirm that assessment practices in these classrooms are largely oriented toward formal testing. Paper and pencil assessments are a routine feature of teaching and learning. Several teachers indicated during informal conversations that they feel pressure to administer frequent written tests to prepare students for the West African Senior School Certificate Examination (WASSCE).

Although written tests are common, implementation varies. Some teachers reported using short tests at the end of lessons or assigning weekly homework as formative checks, but this was not consistent. The item on “setting paper and pencil tests at the end of lessons” received a mean frequency rating of approximately 3.3 (SD ≈ 1.05), which corresponds to “sometimes” to “often.” This suggests that daily or per-topic quizzes are not a universal practice. Instead, most teachers focus on periodic quizzes and term examinations. The findings reflect a largely summative orientation, where assessment occurs at regular intervals rather than as a continuous instructional strategy.

Using Performance Assessment

The study found relatively limited use of performance assessments, including projects, oral presentations, practical investigations, or portfolios, even though curriculum guidelines promote these approaches. When asked about assigning mathematics projects or rich tasks that require students to investigate and present findings, most teachers reported doing so “rarely” or “sometimes.” The most commonly used form of performance assessment was observing and evaluating students’ participation and responses during lessons. The summary of mean frequency and skill ratings for performance and alternative assessments is shown in Table A2 (Appendix).

According to Table A2, “assessing individual class participation” had one of the highest frequency means among performance assessment items, indicating that many teachers regularly observe and evaluate students during lessons. Teachers also reported feeling skilled in using these interactive practices. For example, the mean self-rated skill levels for observing students and asking questions during instruction were above 4.0.

Practices such as student self-assessment and peer assessment were reported somewhat less frequently, with average frequency ratings in the range of 3.6 to 3.8, corresponding to “sometimes” to “often.” Teachers’ self-assessed skill levels in these areas were moderate.

At the lower end of the spectrum were more structured performance tasks. Very few teachers reported using portfolios (collections of student work) to assess progress, and most indicated low confidence in using them effectively. Similarly, collaborative projects or investigations that involve real-world applications of mathematics were not a regular feature of most classrooms. Although some elements of formative assessment, such as classroom questioning, were present, more authentic assessment approaches, including portfolios, self-assessment, and peer evaluation, have not been widely adopted.

Teachers attributed this limited use to factors such as a lack of time for extended projects, large class sizes that make management difficult, and limited emphasis on these methods in final examinations.

Teachers’ Self-Perceived Assessment Skills

Alongside reporting their classroom practices, teachers were asked to rate their skill levels in performing various assessment tasks. The findings indicate that teachers felt most confident in the areas with which they engaged most frequently. In particular, they reported high levels of skill in tasks related to constructing and administering traditional tests. Teachers indicated that they were able to prepare valid paper-and-pencil tests, create different types of questions (including multiple-choice and short-answer questions), administer tests fairly, and grade student work consistently.

They also felt confident in aligning classroom tests with curriculum objectives and ensuring that topics were adequately covered. A majority stated that they often develop a test blueprint or table of specifications, even if they do not use the formal terminology. According to the survey data, most teachers believed they were at least “competent,” if not “highly skilled,” in ensuring the validity and reliability of their classroom tests. For example, they reported checking that their tests reflected taught content and included a suitable range of difficulty. Descriptive summaries of teachers’ reported skill levels by domain are provided in Table 1.

However, it is important to note that other studies (e.g., Kissi et al., 2023; Quansah et al., 2019) have shown that Ghanaian teachers sometimes violate key test construction principles. This suggests that some of the self-ratings may not fully reflect the actual quality of teacher-made assessments.

Teachers reported lower levels of skill in tasks related to data analysis and interpretation. For example, fewer teachers felt confident in analysing test results statistically or using standardised test data to inform instruction. As shown inTable 5, tasks in the Standardised Tests and Data Use domain – including interpreting score reports, conducting item analysis, and using results for planning – were performed less frequently, with most mean frequencies falling within the “sometimes” range. Corresponding self-rated skill levels were also moderate.

The least reported and lowest rated skill areas were tasks such as calculating difficulty and discrimination indices or interpreting norm-referenced scores (e.g., percentile ranks and stanines). Many teachers admitted to having only basic skills in these areas or not performing them at all.

When prompted about statistical analysis, such as computing item difficulty, analysing score distributions, or calculating measures of central tendency and variability, most teachers gave low skill ratings. Although they regularly administer tests, few reported going beyond basic scoring. The concept of using assessment data to adjust instruction remains underdeveloped in many classrooms. To further examine teachers’ competence in test construction, the study explored their responses in the domain of Ensuring Test Validity and Reliability. A summary of their responses is presented in Table 1, where we estimate the mean ratings of assessment practices and skills among teachers.

Teachers reported high frequency and skill in aligning assessments with lesson objectives, covering appropriate content, and ensuring clarity in question phrasing. They also indicated that they regularly review items before administering tests. However, some practices, such as defining performance criteria or rubrics in advance, were less common, suggesting that the routine use of scoring guides is not yet widespread.

Teaching Experience

The results show a small but statistically significant correlation between years of teaching experience and teachers’ overall assessment practice scores (r ≈ 0.13, p < .01, Cohen’s d ≈ 0.27), as well as a similar correlation with self-reported assessment skill (r ≈ 0.14, p < .01, Cohen’s d ≈ 0.28). In practical terms, teachers with more years in the classroom tended to report slightly more frequent use of assessment strategies and slightly higher confidence in their assessment competence. However, the effect sizes were weak. The correlation coefficients aresummarisedin Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.Correlation of Experience with Assessment Practice

| Teaching Experience | Assessment Practice | ||

| Teaching Experience | Pearson Correlation | 1 | .132** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .003 | ||

| N | 511 | 511 | |

| Assessment Practice | Pearson Correlation | .132** | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .003 | ||

| N | 511 | 516 |

Note.**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed).

Table 3.Correlation of Experience with Assessment Skills

| Teaching Experience | Assessment Skills | |||

| Teaching Experience | Pearson Correlation | 1 | .136** | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .002 | |||

| N | 511 | 511 | ||

| Assessment Skill | Pearson Correlation | .136** | 1 | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .002 | |||

| N | 511 | 516 |

Note.**. Correlation is significant at the .01 level (two-tailed).

These findings suggest that teaching experience alone does not automatically result in assessment expertise. This is consistent with research indicating that years of service, in the absence of professional development, may not lead to increased assessment proficiency. In Ghana, it could be expected that experienced teachers, particularly those who taught before the introduction of school-based assessment reforms, might either retain older habits or adapt over time. The data show that teachers with more than 10 years of experience do report somewhat higher self-efficacy, but the differences are small. Notably, many novice teachers (up to four years of experience) reported similar patterns of test-based assessment use, indicating that they may be modelling existing school practices or drawing on their own student experiences. These findings highlight the need for structured professional development in assessment, rather than relying on years of experience to build competence.

Training in Assessment

Participation in assessment-related training emerged as a more influential factor. Teachers were grouped based on whether they had ever attended a workshop or in-service training on assessment. Approximately 36 percent of the sample reported no prior training, while 64 percent had attended at least one.

Teachers who had received training exhibited significantly higher overall frequency scores for assessment practices (mean ≈ 195.6) than those who had not (mean ≈ 188.3), with the difference statistically significant (t(514) ≈ –3.21,p= .001, Cohen’sd≈ 0.29). The difference was more pronounced in self-reported assessment skills. Trained teachers had a higher mean skill score (≈ 206.4) compared to untrained teachers (≈ 196.4), with a stronger statistical effect (t(514) ≈ –4.10, p < .001, Cohen’s d ≈ 0.38). These comparisons aresummarisedin Tables 4and 5.

Table4.Assessment Practice Scores by Training Status

| No. of Training | N | M | SD | t | df | p |

| No training | 185 | 188.3409 | 26.12673 | -3.212 | 514 | .001 |

| At least one training | 331 | 195.6008 | 23.74831 |

Table 5.Assessment Skill Scores by Training Status

| No. of Training | N | M | SD | t | df | p |

| No training | 185 | 196.4404 | 28.51947 | -4.102 | 514 | .000 |

| At least one training | 331 | 206.4181 | 25.29860 |

These results suggest that assessment training is associated with meaningful improvements. Teachers with training were more confident in tasks such as designing diverse assessments, interpreting results, and providing feedback. They also reported greater use of alternative approaches, including project-based assessments and the use of assessment data for instructional planning, although such practices remained relatively limited overall.

The findings support the argument that building assessment competence through structured training plays a key role in shaping teacher behaviour. This is consistent with calls in the literature for targeted professional development in formative assessment and data use (Oguledo, 2021; Van der Nest, 2018). Most teachers in this study reported attending only one or two training sessions, usually in the form of brief workshops. Even this limited exposure was associated with noticeable differences in both practice and self-efficacy, suggesting that more sustained and intensive training could yield even greater improvements.

West Africa Examination Council Marking Experience

About 22 percent of the teachers in the sample reported having served as examiners or assistant examiners for the WASSCE mathematics examination. This role involves participating in coordination meetings and marking student scripts under the supervision of the WAEC. It washypothesisedthat such experience might be associated with differences in teachers’ classroom assessment practices, possibly making them more test-focused or more proficient in formal assessment techniques.

The data, however, showed no statistically significant difference in overall assessment practice between teachers who had participated in WAEC marking and those who had not. Both groups reported similar frequencies in the use of tests and other assessment forms. This suggests that external examining, which is inherently summative, does not necessarily translate into differences in how teachers assess students in their classrooms.

There was a slight indication that WAEC examiners rated their assessment skills marginally higher (mean ≈ 205.1) than non-examiners (mean ≈ 201.9), but this difference was not statistically significant at the 0.05 level. A comparison of their classroom assessment practices with those of non-examiners is presented in Table 6.

Table 6. WAEC Exam Marking Experience

| WAEC marking | N | M | SD | t | df | p |

| Never been a participant | 369 | 201.9815 | 28.20367 | -1.299 | 513.711 | .195 |

| Participated at least once | 146 | 205.1279 | 23.28752 |

One interpretation is that the WAEC marking process, while helpful in understanding national examination standards, focuses primarily on scoring consistency and accuracy instandardisedresponses. As a result, it may reinforce familiarity with exam-style assessments and rubrics, rather than broadening teachers’ use of diverse or formative assessment methods. The data did not indicate any spillover from examiner experience to the adoption of alternative assessment practices.

Gender and Qualifications

The analysis also examined whether assessment practices and self-assessed skills differed by gender or academic qualification. The sample included both male and female mathematics teachers, although males constituted a higher proportion, reflecting national trends in mathematics education staffing. T-test results are presented in Tables 7 and 8.

Table 7.T-test Results of Assessment Practices by Gender

| Gender | N | M | SD | t | df | p |

| Male | 438 | 193.1935 | 25.17503 | .798 | 507 | .425 |

| Female | 71 | 190.6516 | 23.13833 |

Table 8.T-test results of assessment skills by gender

| Gender | N | M | SD | t | df | p |

| Male | 438 | 203.7910 | 26.67638 | 2.016 | 507 | .044 |

| Female | 71 | 196.8419 | 28.56405 |

There were no statistically significant gender differences in either assessment practices or perceived skill. On average, male and female teachers reported similarbehavioursand confidence levels. This suggests that gender was not a determining factor in theobserved assessment patterns and that both groups share similar support needs forimproving and diversifying assessment approaches.

Regarding qualifications, an independent samples t-test showed no significant difference between teachers holding a master’s degree (M = 3.14, SD = 0.47) and those with a bachelor’s degree (M = 3.09, SD = 0.51) in terms of assessment practice or skill,t(514) = 1.02,p= .309, Cohen’sd= 0.09. Although some master’s-qualified teachers may have received advanced training in educational measurement, this was not reflected in markedly different classroom practices. The number of teachers with postgraduate qualifications was relatively small (n = 65), and many of these qualifications may be in subject content rather than education.

This finding may reflect the relatively recent incorporation of assessment-focused coursework into postgraduateprogrammesin Ghana. Overall, academic qualification did not emerge as a significant factor distinguishing teachers’ assessmentbehavioursor their self-perceived competence.

Multiple Regression Analysis

To examine the unique contributions of all background factors simultaneously, two multiple linear regression models were run with assessment practice and assessment skill scores as the outcome variables. The overall regression model for assessment practice was statistically significant,F(5, 510) ≈ 5.5, p < .001, with R² ≈ 0.05 (adjusted R² ≈ 0.04). Similarly, the model for assessment skill was significant,F(5, 510) ≈ 7.7, p < .001, with R² ≈ 0.07 (adjusted R² ≈ 0.06). Table 9 presents the standardized regression coefficients (β) for each predictor in both models. Consistent with the bivariate results, participation in assessment training was the only significant predictor of both practice and skill outcomes (β ≈ .24 - .30, p < .001). Teaching experience had positive but small coefficients that did not reach statistical significance when controlling for the other variables (p > .05). Gender, WAEC examiner status, and academic qualification also showed no significant unique associations with either assessment practice or skill (all p > .05). In combination, these five background factors explained only a modest proportion of variance in teachers’ practice and skill scores (around 5-7%), reinforcing that professional development exposure was the dominant differentiator.

Table 9. Multiple Linear Regression Predicting Assessment Practice and Skill

| Predictor | β (Practice) | p (Practice) | β (Skill) | p (Skill) |

| Training (assessment PD) | .24*** | .000 | .30*** | .000 |

| Experience (years) | .08 | .100 | .09 | .060 |

| Gender (Male) | –.05 | .320 | –.07 | .150 |

| WAEC examiner (Yes) | .04 | .450 | .05 | .250 |

| Qualification (Master’s) | .02 | .730 | .01 | .880 |

Note.N = 516. Unstandardized intercept not shown. β = standardized coefficient.p-values(two-tailed) are for the coefficient tests. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .00; no other predictors were significant atp* < .05.

Summary of Findings

The findings reveal a clear pattern: mathematics teachers in Ghanaian senior high schools overwhelmingly rely on traditional test-based assessments, particularly written quizzes and examinations, and report the highest levels of competence in designing and administering these forms of assessment. In contrast, alternative and formative assessment practices, such as projects, portfolios, peer assessment, and the use of assessment data for instructional improvement, remain underutilised and are associated with lower self-perceived skill. Of the background variables examined, participation in assessment-related training emerged as the most influential factor associated with improved classroom practice and greater confidence. Teachers who had received professional development reported broader assessment repertoires and higher skill levels, even when training exposure was limited. By contrast, years of teaching experienceand involvement in national examination processes (such as WASSCE marking) were not significantly associated with differences in classroom assessment behaviour. These findings suggest that assessment competence does not simply develop through experience or proximity to summative processes, but rather through intentional training and support. This pattern aligns with international evidence that improving assessment practice requires more than structural exposure to tests; it demands sustained professional development to shift teachers’ pedagogical orientation and enhance their confidence in diverse assessment methods. The discussion that follows examines these findings in relation to global literature and considers their implications for policy, teacher preparation, and capacity-building in mathematics education.

Discussion

Viewed through the study’s conceptual framework, these findings suggest a critical interplay between assessment practice, perceived assessment skill, and broader contextual factors. Although teachers reported high levels of confidence in traditional assessment methods, their skill ratings declined significantly in areas involving data analysis, interpretation, and feedback for instructional improvement. This discrepancy aligns with prior research, which shows thatteachers often feel confident using conventional assessments because familiarity breeds comfort, whereas they report lower confidence with formative or performance-based methods (Amirian, 2025;Atjonenet al., 2022). The study thus reveals a clear gap between teachers’ frequent practices and their limited use and perceived skills in formative and alternative assessments. Addressing this gap is crucial for achieving genuine changes in classroom assessment practices.

Furthermore, the results underscore the crucial role that professional development plays in shaping teacher assessment practices. Participation in assessment-related training was strongly associated with enhanced classroom practice and increased self-reported skills, even among teachers with limited exposure to such training. This finding aligns with broader international literature highlighting that effective assessment reform requires sustained professional learning—not only to build technical skills but also to cultivate critical reflection on assessment’s purposes and practices (Alonzo et al., 2021). Without targeted and ongoing professional development, teachers tend to adhere to existing practices, reflecting either the culture of their institutions or their own experiences as students. The implication for policymakers and education leaders is clear: for reforms such as Ghana’s SBA policy to become genuinely transformative, teacher capacity must be prioritised through intentional, reflective, and continuous professional development.

In contrast, teaching experience alone demonstrated only a weak association with improved assessment practices or increased skills. This suggests that simply spending moreyearsteaching does not necessarily translate into stronger assessment competencies or more sophisticated classroom practices. The international literature corroborates this, noting that experience, absent targeted professional learning, typically yields minimal improvement in teachers’ assessment literacy (Herppichet al., 2018; Klinger et al., 2015). Similarly, serving as an examiner for national examinations (WAEC marking) was not associated with any significant changes in teachers’ everyday classroom practices. Although one might expect examiner roles to offer insights that enhance formative assessment, the data indicate teachers compartmentalise this summative experience, maintaining familiar routines rather than adopting new practices. These results reinforce research on teacher identity, indicating that roles perceived as externally imposed or disconnected from daily classroom realities rarely foster deep pedagogical change (Sayac& Veldhuis, 2022). Sustainable change appears more likely to occur within ongoing, reflective professional communities embedded within schools rather than through isolated, externally driven experiences.

No major differences were found based on either gender or academic qualification in teachers’ assessment practices or self-assessed skills. On average, male and female teachers reported similar assessment behaviours and confidence levels, and holding a master’s degree did not correspond to significantly higher competence than holding a bachelor’s degree. This suggests that these demographics were not key differentiators of assessment practice or skill in this context. Nevertheless, the lack of an observed advantage for teachers with advanced degrees highlights the need for postgraduate teacher education programmes to place stronger emphasis on contemporary assessment principles and practices. By doing so, higher academic qualifications might better translate into meaningful improvements in classroom assessment.

Overall, the Ghanaian case aligns with recent international scholarship, which shows that effective assessment reform depends on coherence across the curriculum, pedagogy, assessment frameworks, and teacher preparation programs(Zeichner et al., 2024). Top-down policies alone, no matter how progressive, are unlikely to succeed unless teachers fully understand, internalise, and actively participate in shaping the reform process. This has been observed in multiple international contexts, including France, where similar gaps between policy and classroom practice were documented bySayacand Veldhuis (2022). Such findings indicate that policymakers must invest not only in clearly articulating reform goals but also in creating supportive structures, such as ongoing professional learning communities and opportunities for collaborative reflection.

Conclusion

This study examined the assessment practices and self-perceived skills of senior high school mathematics teachers in Ghana. It applied a conceptual framework that differentiates between the frequency of assessment activities (practice) and teachers’ perceived competence in carrying them out (skill), while accounting for both contextual and teacher-level factors.

Findings indicate that traditional assessment methods, including quizzes, class tests, and end-of-term examinations, remain the most widely used. Teachers reported the highest confidence levels in conducting these familiar, test-based activities. In contrast, formative and alternative strategies were employed less often and were associated with lower levels of self-assessed competence.

Of the various background variables considered, participation in assessment-focused professional development emerged as the factor most strongly associated with both practice and confidence. In comparison, teaching experience and WAEC examiner roles showed minimal associations with either dimension. These results highlight the pivotal role of sustained professional learning in improving assessment quality and teacher self-efficacy.

The study emphasises that reforms such as School-Based Assessment (SBA) demand more than policy directives. Effective implementation requires structured teacher support, including training, collaborative learning communities, and alignment between curriculum objectives and assessment methods. In Ghana’s high-stakes examination environment, reform must also entail changes to examination formats that encourage more diverse assessment practices in the classroom.

At the school level, teachers are encouraged to incorporate low-stakes strategies such as formative quizzes, exit tickets, and classroom reflections, not only for assigning grades but also to enhance learning. School leaders can support this shift by promoting mentorship, peer observation, and collaborative dialogue on assessment.

Ultimately, the clear association between training and improved assessment underscores the necessity of embedding assessment literacy within both pre-service and in-service teacher education. Beyond technical proficiency, this requires a shift in perspective: understanding assessment as an instrument for advancing learning rather than merely measuring outcomes.

Recommendations

Future research should aim to empirically test the relationships suggested by the framework using structural equation modelling or path analysis to examine the direct and mediated relationships of training, experience, and systemic context with assessment behaviour and competence. Longitudinal designs could provide further insight into how assessment practices and skills evolve, particularly in response to sustained professional development or policy shifts. Mixed-methods approaches incorporating classroom observation, teacher interviews, and document analysis would help triangulate findings and deepen understanding of the interplay between assessment beliefs, capabilities, and constraints in practice.

Limitations

This study has some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, although the conceptual framework guided the analysis, only selected relationships among variables were empirically tested using regression. The full set ofhypothesisedrelationships was not validated using an integrated modelling approach such as structural equation modelling. Second, although both self-report survey data and a subset of classroom artefacts were used, reliance on teacher self-report introduces potential social desirability bias. The absence of classroom observations means some practices could not be independently verified. Third, the cross-sectional design prevents causal inference, limiting the ability to draw conclusions about directionality or change over time. Fourth, because teachers were sampled from multiple schools, school-level influences such as leadership, culture, or policy context were not modelled. No multilevel analysis was conducted. Finally, the absence of multivariate analyses such as MANOVA may limit the detection of joint effects across multiple assessment domains. Addressing these limitations in future research through longitudinal, multilevel, and mixed methods designs would provide a more comprehensive understanding of mathematics teachers’ assessment practices and their determinants.

Ethics Statement

This study received clearance from the Ghana Education Service (GES). All procedures complied with established ethical guidelines for social science research. Informed consent was obtained from all participants for the use of anonymised data in publications arising from this study.

I gratefully acknowledge the contribution of the trained research assistants who supported data collection during the fieldwork phase.

Generative AI Statement

No generative AI tools were used in the writing of this article.